The Water Doctor, by Edgar van Heemskirk, ca.1760-1770 (detail)

To start our blogging journey into the world of 19th century folk medicine, we’re diving headlong into one of the less savoury alternative medical practices: water casting. As the name suggests, water casting (or uromantia, or uroscopy) involved the visual examination of a patient’s urine to divine what was wrong with them. It dates back to the early medieval period, and perhaps even further, and was a popular practice across early modern Europe when physiological and epidemiological knowledge were otherwise very limited. It was even namechecked by Shakespeare, when he had an embittered Macbeth exclaiming to his physician: “If thou could’st Doctor, cast/ The water of my land, find her disease/ And purge it to a sound and pristine health/ I would applaud thee to the very echo” (Macbeth, act 5, scene 5). A less well-known poet, John Taylor – appropriately known as the Taylor the Water Poet – confirmed uromantia’s popularity half a generation later when he wrote disparagingly of a ‘country lady’ who, in her love of luxury and fine living: “Lives by deceit, exiling plain simplicity./ A face like Rubies mix’d with Alabaster/ Wastes much in Physic, and her water-caster”.

But despite its popularity, water casting was already under siege as a serious medical practice by the time Taylor was writing his verse. In 1837, for example, Thomas Brian, M.P., published a strikingly-titled pamphlet; The Pisse-Prophet, or Certain Pisse-Pot Lectures, specifically to expose: “the old fallacies, deceit, and jugling of the Pisse-pot science, used by all those (whether Quacks and Empiricks, or other methodicall Physicians) who pretend to know Diseases by the Urine”; and only a few years’ later, Humphrey Brooke, MRCP, wrote, Ugieine or A Conservatory of Health to persuade the public that: “erroneously … do People imagine, that in the Urin is contained the ample understanding of all things necessary to inform a Physician … the best whereof do leave devining thereby as false, and out of measure uncertain; the most ignorant and deceitful only do practise it”.

Given this early scepticism, it is perhaps a little surprising to find that uroscopy not only survived into the 19th century, but into the 20th as well.

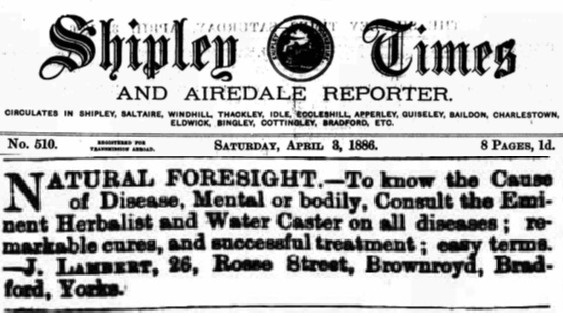

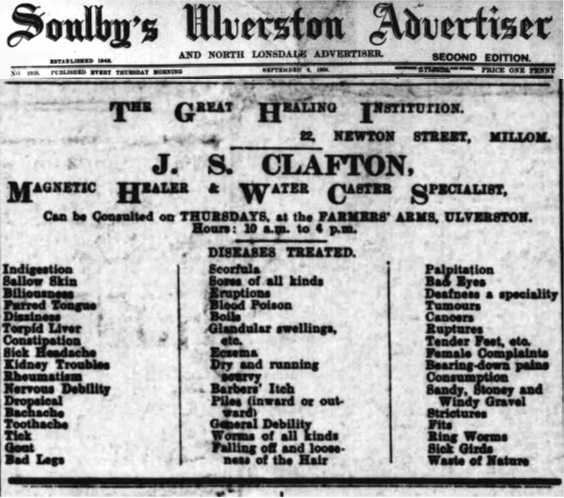

Lambert’s advert from 1886 suggests he was still very much at the esoteric end of uromantia, as he describes himself as a diviner with “NATURAL FORESIGHT”. In this, he seems to have had something in common with Henry Harrison of Leeds who, in 1856, gave evidence at the murder trial of William Dove. When asked his occupation, Harrison told the court (to some laughter): “I am a dentist, or rather water caster, and I have done a little astrology” (Derbyshire Advertiser & Journal, 25 July 1856). In the event, it emerged that Harrison was far more than any of these things. As our own Owen Davies has shown, Harrison was a notorious wise man (a “wizard” according to several newspapers at the time) and he held Dove in his thrall, persuading him that, through sorcery, he could get him off the charge of murdering his wife by poison. On the other hand, by 1904, J.S. Clayton was very much situating his practice at the cutting edge of the new ‘scientific’ medicine, as a “Magnetic Healer and Water Casting Specialist”. Despite the valiant efforts of Clayton and others like him to bring uroscopy into the modern world, he was largely unsuccessful, and within ten years the folklorist Elizabeth Wright (in Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore (OUP, 1913)) was noting of water casters that “none of them are left now”, even in the uromantic heartland of Yorkshire’s West Riding.

It seems, then, that notwithstanding the revival of alternative medicine over the past few decades, water casting is one of those practices which has been flushed from the medical landscape forever.

* On Harrison the water caster and wise man, see Owen Davies, Murder, Magic, Madness: The Victorian Trials of Dove and the Wizard (Routledge, 2014). For further reading on the long history of water casting, see Michael Stolberg, Uroscopy in Early Modern History (Ashgate, 2016).