This month we have a guest blog from Dr Julie Moore on the career of Isaac Chamberlain of Hertford. Look out for the second instalment next week…

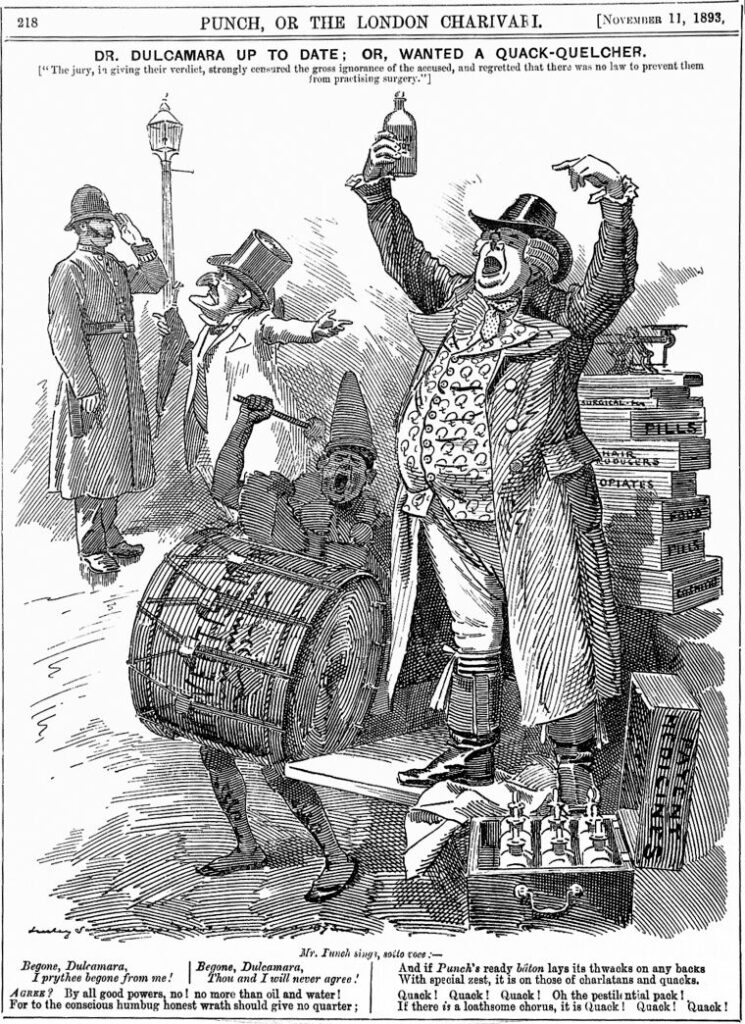

Parody of a quack medicine vendor from Punch, 1893.

Quacks were the focus of much ridicule as well as opprobrium in 19th century periodicals

When Isaac Chamberlain, herbalist, dentist and astrologer, died in 1879, a local newspaper, the Herts Guardian and Agricultural Journal, acknowledged his career with a two-part obituary which extolled his virtues as a healer and one who extended charity to those in need of his services (26th April and 3rd May 1879). In contrast, a local rival, The Hertford Mercury and Reformer, remained silent on his passing, perhaps in the spirit of: ‘if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all’. For whilst the Tory supporting Guardian cast Chamberlain in the role of a friend to the poor and one who gave hope to those deemed incurable by ‘regular practitioners’, the Liberal supporting Mercury used his many appearances in court to highlight the dangers of quackery so “that the ignorant may be protected in spite of themselves”. (23rd October 1841).

Chamberlain’s career demonstrates the opportunities available to those who dealt in pills and potions for the many people who suffered ill-health in the 19th century. Born in 1801, his first career was as a Journeyman Butcher, living in one of the poorest parts of the county town of Hertford. By 1841, although still working as a butcher, he had developed a sideline in treating his neighbours and had developed enough of a reputation for potential customers to travel from far beyond his local area.

In September 1841, Elizabeth Chymist made the ten-mile journey from her home in Cheshunt to consult Chamberlain about a tumour on her breast. She had previously been treated by a Dr. Kerrison in London. He had prescribed some pills and an ointment of sweet oil and camphor, but these had made little difference and so she decided to consult Chamberlain. Wife of Samuel, a baker, and mother to four children, she was expecting her eighth child when she arrived in Hertford. Chamberlain told her that what she had was a ‘stone cancer’ and that he could cure it. To this end, she moved into lodgings in Hertford and he began a treatment of applying a caustic ointment and then scraping away the dead tissue. This went on for six weeks until Elizabeth went into premature labour and her baby was delivered at only seven months. At this point her landlady called the local doctor who prescribed a poultice for the wound, but only to relieve her pain as he was convinced from the sight of her wound that her case was hopeless. Poor Elizabeth, laid low by a heavy cold, worn out from childbirth and with a breast described as gangrenous, died later that night. Right to the end she had faith in Chamberlain – she had gone so far down that path that perhaps she could not bear to think she had taken the wrong turning. Her post-mortem suggested that the tumour was benign, although that may have been a case of qualified doctors laying on the pain as an attack on quackery.

The verdict of the inquest was one of manslaughter against Chamberlain. The gruesome details of his treatments, the emphasis throughout on his occupation as a butcher, together with the sight of poor Elizabeth laid out for the jury to examine, would seem to have made any other verdict redundant. At the subsequent trial Chamberlain was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to one year in prison.

Both the County Press and the Hertford Mercury and Reformer carried editorials on the case, warning against the dangers of quackery. The County Press took the line that it was really the fault of the credulous that men like Chamberlain were allowed to flourish, and took a rather optimistic view of the charitable natures of ‘regular’ practitioners:

Any other but a regular medical man … has no right to practice medicine of surgery – he is a rascal who does so, and they are fools who allow him to ‘practice’ on them; there is no reason why poor people should resort to those base knaves, because, thank Heaven, our regular practitioners have as high a character for liberality and benevolence, as for skill and intelligence. (19th March 1842)

The Mercury took a similar line and its headline of ‘The Butcher Surgeon’, left no one in doubt as to where their sympathies lay. (23rd October 1841).

Yet, Chamberlain would seem to have already built quite a following. Four months into his sentence, a petition was raised to send to the Queen asking for his release and highlighting his standing as a Wesleyan Methodist and one of ‘unimpeachable character’. The petition garnered 130 signatures, and perhaps most surprisingly of all they were headed by Elizabeth Chymist’s husband and her parents. The petition was unsuccessful. (HO18/83/65 1842)

To be continued…