On 20 November 1902 a child was born at Wreyland, in Devon, suffering from a rupture (the term has several meanings but likely a hernia in this case). Word of the birth eventually made its way to Cecil Torr, a local antiquarian, but with doctors unwilling or unable to act, Torr assumed that the child had died. He was surprised later to encounter the father who, on being asked about the child’s welfare, noted that he was “a sight better since us put’n through a tree”.

According to Torr’s account, the family had split an ash tree down the middle, wedged open the crack to create a clear way through the whole trunk, and “as the sun rose, they passed it [the child] three times through the tree, from east to west”. Subsequently the tree was bound back up and as it grew back together again, “so would the rupture heal also”. Stunned, a sceptical Torr wondered why the family would undertake this ritual. The father, though, retorted that this was the normal way of dealing with physical injuries and breakages and thought that his own method probably did more good than “sloppin’ water over’n in church”.

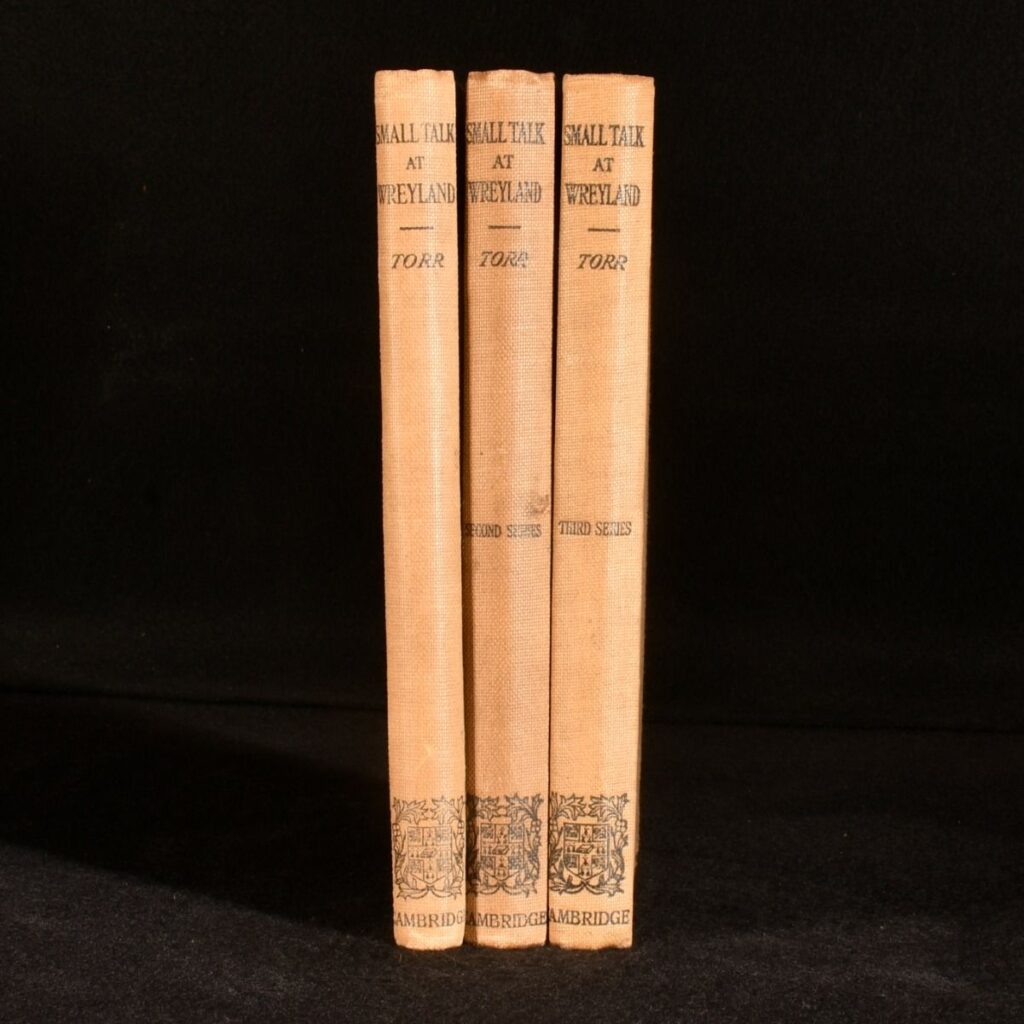

Torr’s report of the tree-splitting remedy appears in his local observations and memories entitled Small Talk at Wreyland, which were published periodically between 1918 and 1923 and then, finally, in a single abridged volume in 1925. As he himself noted, Torr wrote Small Talk because, as “older natives” of his small area of Devon died, “I hear people lamenting that so much local knowledge has died with them, and saying that they should have written things down”. Worried that “this might soon be said of me”, he began collecting local and family lore initially for his own private archive, but was soon persuaded that there was sufficient interest in his material to make it widely available; clearly, he was right.

An upsurge of interest in autobiography, diarisation, and memoirs from the 1860s was part of what Martyn Lyons has understood as the democratisation of life writing. There were hundreds of Torrs, spread across the class and spatial spectrum. In this sense such sources provide us with a unique lens through which to view health, medicine and alternative healing.

Cecil’s three volumes are neither a record of particular lives, nor a comprehensive rendering of the life, character, and culture of Wreyland. But in a sense, this is the point. At Alternative Healers, we are interested in accounts where alternative medicine appears as part of the casual and everyday observation of the authors. In Torr’s writings we have not been disappointed, with just over 60 detailed references to sickness and cure spread across these remarkable volumes.

Returning to the story of the child and the ash tree, it is clear that folk remedies retained sustained traction (at least in rural areas) only two decades before the inception of the NHS. Given the density of Torr’s commentary on healing throughout his writing, putting the boy through a tree may also point to something distinctive about healing culture in south-west England, an issue we continue to explore in the project.

On the other hand, the hundreds of memoirs, memorials of place, autobiographies and ethnographies that have been read for our project also point to something more important. In almost every English and Welsh county in the period after 1834, we find exactly the same story about splitting or injuring trees and passing the sick and injured through, around or up and down them. Michael Courtney recorded the practice in Cornwall in 1890. George Ewart Evans noted the continuance of the practice in his ethnographies of Suffolk people and places in the 1920s. The Vicar of Rothersthorpe (Northamptonshire) lent one of his trees for this purpose in 1908 where formal medical intervention had failed. And in the village of Toot Baldon, near Oxford, the family records of the Barrett dynasty record several instances of this practice using elm trees during the 1930s. The scars on those same trees were visible right up until they were felled because of Dutch elm disease, and in a delicious irony they formed an avenue up to the church gates.

Perhaps such folk remedies were ‘just’ a hangover from a rural past as villages and villagers “caught up” with modern medicine. Certainly, Sue McDowall records a number of similar instances in the pages of Folklore from the later nineteenth century onwards. But evidence from elsewhere suggests not. South Korea’s national initiative to establish healing forests speaks to both shared folk traditions and an increasing global awareness of the spiritual, mindfulness and healing power of trees and tree environments. The first large-scale initiatives of this sort in Britain – interestingly, on the edges of towns and cities – are just beginning, with aspirations to move beyond mindfulness and into the practical healing power of bark, sap, wood and pulp.

We cannot know whether Cecil Torr really was a sceptic, but his volumes demonstrate that he was prepared to try almost any remedy he could get his hands on when he needed it. Who knows: if he was still writing now, we might even have his first-hand account of a visit to South Korea.

For further reference, see:

- Martyn Lyons, The Writing Culture of Ordinary People in Europe c.1860 – 1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

- Sue McDowall, Plants before the Revolution: Food, Remedies, Festivals and Beliefs in Pre-Industrial England (Hurstwood Publications, 2018)

- Won Sop Shin, ‘Forest Policy and Forest Healing in the Republic of Korea’, available at https://foresttherapyhub.com/

- Cecil Torr, Small Talk at Wreyland, 3 Volumes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1918, 1921, and 1923.

- Forestry England: https://www.forestryengland.uk/article/why-forests-are-good-health-and-wellbeing