Historians of medicine often talk about the ‘medical marketplace’ in the 18th and 19th centuries, as we have ourselves many times in our work. Generally, when they use that phrase they mean to signify the huge (often bewildering) range of alternatives that people accessed to address ill-health: from college-trained surgeons and physicians, through dispensaries, medical charities and other institutions, and on to alternative practitioners and provisioners such as the ones we have looked at in our blogs. But of course, the phrase has another, very specific meaning which is often neglected in the literature; it also describes a physical space in a town or city where people bought remedies, cures and ingredients for their own domestic medicines.

In early modern London, for example, there existed a number of markets which were specifically designated for the sale of herbs (sometimes alongside fruit and vegetables and other foodstuffs), many of which would have been bought and sold for medicinal use. Around Cheapside, the church of St. Bennet, in Gracechurch Street, was also known as ‘Grass Church’ (hence the corrupted street name) owing to the presence of a herb market in its environs. Bucklersbury, in the dead centre of the city near what is now Bank underground station, was also known as a place which was “inhabited almost entirely by druggists, and vendors of herbs and simples”. Hence, Falstaff’s arch description in The Merry Wives of Windsor of men “that come like women in men’s apparel, and smell like Bucklersbury in simple time” (a ‘simple’ being a vegetable-based, single-ingredient remedy).

Even earlier, during the fourteenth century, the market at Cheapside was divided between the sale of meat, between Great Conduit Street and Bread Street, and herbs, from Bread Street to St. Mary-le-Quern. After the Great Fire, in 1666, London’s provisioning markets were repurposed, partially relocated, and more closely regulated than they had been before, and space at Newgate, Leadenhall and Honey Lane markets was specifically put aside for gardeners and herbsmen and women. But the greatest innovation at that time was the development of the fruit, vegetable and herb market at Covent Garden.

The very name of the area gives us a hint to its history; ‘Covent Garden’ being a corruption of ‘Convent Garden’, so-named because of the presence of gardens and orchards belonging to Westminster Abbey and Convent from the thirteenth century onwards. In the sixteenth century, Inigo Jones created a fashionable square of fine houses on the site, but by the 1650s a small open air fruit and vegetable market had once again gained a foothold alongside these fine residences. In 1670, the Earl of Bedford obtained a charter for the market and it grew rapidly, becoming London’s largest fruit and vegetable market and the only one that specialized in greengrocery. As a result, it also became London’s largest herb market.

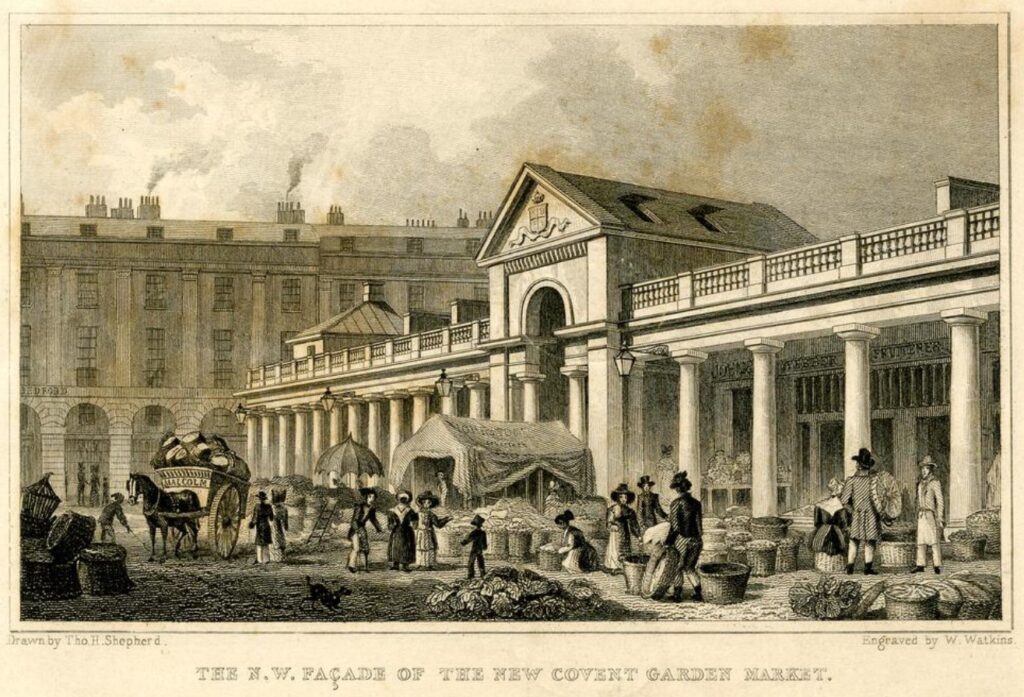

The association of Covent Garden with herbs and simples was therefore established very early on, and by the nineteenth century the fruit and vegetable market was a vibrant and bustling part of the London scene, as well-known for its brothels and bars as for its medicinal ingredients. In 1830, the familiar market hall was built to provide shelter for the traders and to create a greater sense of permanence and respectability, and by the twentieth century a number of shops selling herbs and remedies were also thriving, including perhaps the best known and most successful of all: Butler and McCulloch’s.

Butler, McCulloch and Co. was originally established way back in 1735 as a herb and seed warehouse by James Butler at “ye Sygne of Ye Thistle and Crown” in Covent Garden, but by the end of the nineteenth century the business had expanded to occupy a substantial premises on South Row in Covent Garden Market. Even today, there is evidence on the fabric of the building of their long-term presence. According to Grace’s Guide, by the twentieth century they were “wholesale importers and exporters of all kinds of culinary and medicinal herbs, distillers of perfumed and medicinal waters, and essence manufacturers”; and they were regularly name-checked by pharmaceutical and other journals as favoured suppliers of more exotic herbal ingredients, such as Quillai Bark (to prevent baldness), Sarracenia (for the treatment of small pox) and Kousso, or African Redwood (for the treatment of tapeworm).

Butler and McCulloch’s were, as their early description suggests, also very much involved in the horticultural trade, and they supplied seeds and plants to gardening enthusiasts up and down the country. In 1872, they even received thanks from the London Parks’ and Commons’ Committee for a donation of a quantity of irises which were planted in Finsbury and Southwark parks. However, it was for their wide stock of herbs, herbal medicines and infusions that they were best known. Unfortunately, Butler and McCulloch gained a degree of unwanted notoriety in 1859 when a group of young lads (“well known market thieves”) stole a jar of syrup of belladonna (deadly nightshade) from a hamper outside their store and, thinking it was liquorice extract, mixed it with water and sold it to their friends. Many of their young customers ended up in hospital, some in “a raving state”, along with two of the boys who had taken some of their own medicine. These two were later removed forcefully from their sick beds by their parents who, according to the Holborn Journal, “pushed [them] into the witness box”; but it was found that they were still too ill to give evidence. The young thieves ended up in a reformatory; we do not know what became of their unfortunate victims.

Covent Garden was thus the site of Britain’s largest and most famous fruit, vegetable and herbal market for centuries. In the mid-1970s, it was moved to Nine Elms, in Battersea, and was renamed the New Covent Garden Market. This was a move that was entirely in keeping with its historical traditions, Battersea Fields being the site of many of the gardens which supplied the old market with much of its produce, including herbs and simples – hence the old saying about the foolish and deluded, “send them to Battersea to be cut for the simples”. But every large town and most of the smaller ones, too, would have had their own herb market; and, if not, they would have had their regular herb sellers who set up stall in the general marketplace and supplied the populace with remedies and ingredients for domestic medicines.

So it is that the ‘medical marketplace’ is a vibrant historical location in more ways than one: in a general sense, it is where people sought out medicines and treatments for ill-health from a whole range of possible alternatives; but we must not forget that it was also a specific physical space, the place locally where people bought and sold herbs, simples and traditional remedies week-in, week-out for many centuries.