Here they stand, brothers all,

All the sons—divided they fall.

Here awaits the birth of the son,

The seventh, the heavenly, the chosen one.

Here, the birth from an unbroken line:

Born the healer—the seventh—his time.

Unknowingly blessed, and as his life unfolds,

Slowly unveiling the power he holds.

These evocative lines, reminiscent of an ancient poem or prophetic verse, are in fact lyrics from the song Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, written by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden. This song serves as the title track of their seventh studio album, Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, released in 1988. The album achieved substantial commercial success, selling approximately 3.5 million copies worldwide.

The concept behind the album and its title was inspired not only by its position as the band’s seventh release but also by the 1987 novel Seventh Son by Orson Scott Card. This historical fantasy work, which had a notable influence on Iron Maiden’s songwriter Steve Harris, is the first volume in the Tales of Alvin Maker series. The novel combines elements of alternate American history with folklore and myth, heavily drawing upon the motif of the “seventh son of a seventh son” – a folkloric figure often ascribed extraordinary powers.

Both Iron Maiden’s album and Card’s novel exemplify the enduring presence of this folkloric archetype within popular culture. The mythology surrounding the seventh son of a seventh son, particularly in relation to healing and divination, has persisted across Europe for centuries.

This tradition has deep roots in European folklore, where the number seven has long been associated with spiritual power, perfection, and completeness. Within this framework, the seventh son of a seventh son was believed to be born with innate healing abilities. In Britain, such beliefs blended pre-Christian and Christian traditions, including the “royal touch,” whereby monarchs were thought to cure diseases like scrofula simply by touching the afflicted. These royal rituals symbolically linked divine favour, hereditary lineage, and the power to heal.

Outside royal circles, the seventh son often emerged in folk medicine as a domestic and community healer. In Britain and Ireland, particularly in rural areas or overcrowded urban centres, the seventh son was thought to possess unique gifts. Healing through touch, charms, or rituals became associated with these individuals. Local traditions affirmed their status as repositories of folk wisdom, handed down through generations.

The seventh son also exemplified how family roles and birth order influenced cultural expectations. Healers were seen as both familiar and extraordinary; rooted in everyday domestic life, yet touched by supernatural power. Oral storytelling helped preserve this narrative, reinforcing communal identity, especially in times of rapid social change.

Although less common in folklore, the concept of the “seventh daughter of a seventh daughter” also appeared, often linked to healing and intuition. These female counterparts reflected both the marginalisation of women in historical narratives and the continued association of femininity with health and caregiving.

Beyond myth, the figure of the seventh son became a recognisable presence in British society, particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Often intertwined with the alternative medical marketplace, seventh sons were viewed by many as legitimate healers, though met with scepticism by the medical establishment.

In the British cultural consciousness of the 19th and early 20th centuries, seventh sons of seventh sons were believed, like royalty, to possess the ability to cure scrofula by touch. This practice was said to have originated with Edward the Martyr – or, according to a Cork Examiner article dated 10 June 1844, with Edward the Confessor – and was maintained up to the era of the last Stuart monarchs. A formal liturgy was even devised for the occasion, with a bishop presiding over the ceremony. Charles II is recorded as having touched 92,107 individuals over a span of 20 years, sometimes healing as many as 500 or 600 people in a single event. The ecclesiastical historian Jeremy Collier referred to this as an “hereditary miracle.”

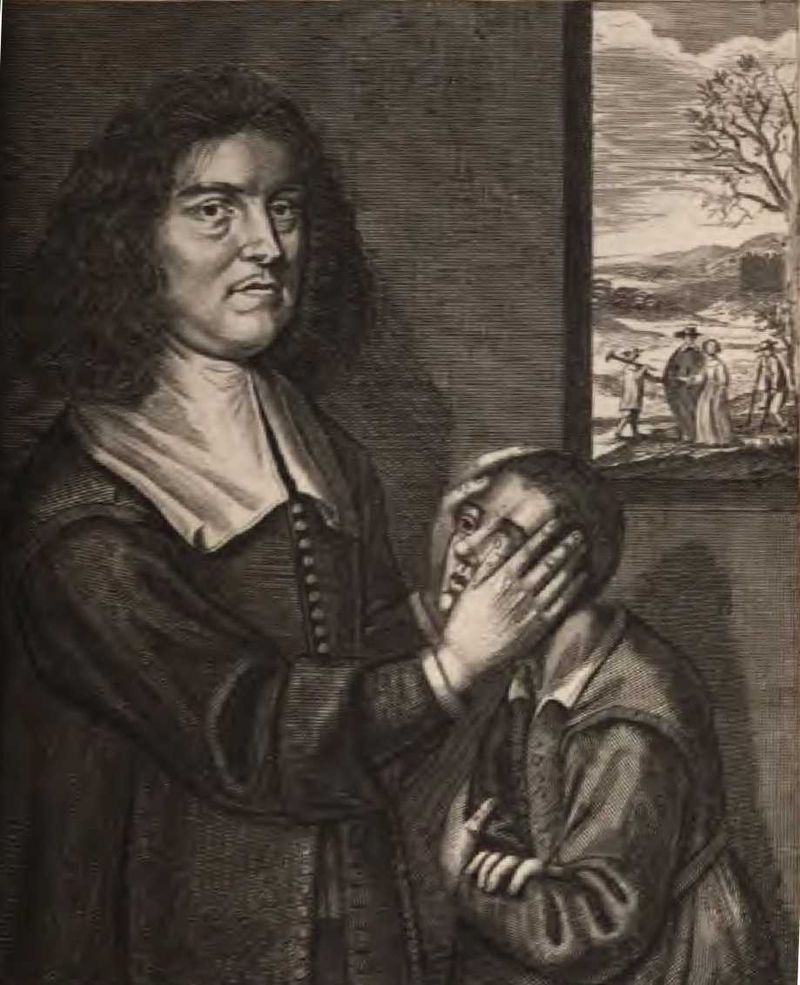

Initially, the supposed healing virtue was believed to be an exclusive prerogative of the monarchy. However, during the reign of Charles II, a number of individuals known as “strokers” emerged, claiming to possess the same healing gift by virtue of being the seventh son of a seventh son. This belief was thought to have gained traction partly because Charles II himself was considered – through a somewhat convoluted genealogical interpretation – to be a seventh son of Henry VII. This lineage includes Margaret, Queen of Scotland (Charles’s daughter, counted as the second in the sequence), James V of Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI and I, Charles I, and Charles II himself as the seventh.

Eventually, other figures claiming similar abilities emerged. Among the most notable was Valentine Greatrakes (1628–1682), an Irish faith healer known as “the Stroker.” His fame and healing demonstrations challenged the royal monopoly on miraculous cures, and many believed he had powers as a seventh son. Greatrakes’ popularity marked a turning point in public trust – from divine monarchy to individual folk healers.

In Lancashire, the belief in the seventh son took an even more unique form. Folklorist Simon Young, in his 2019 article ‘What’s Up Doc? Seventh Sons in Victorian and Edwardian Lancashire’, published in the journal Folklore, identified cases in Victorian-era Blackburn where seventh sons were formally named “Doctor” at birth. This was not a nickname but an actual given name, reflecting belief in their healing destiny. Census data confirms that many boys named “Doctor” were indeed seventh sons, cementing the link between naming practices and folk tradition.

Despite their popularity, seventh sons were often criticised by the press and scientific authorities. An 1848 article from the Weekly Dispatch (10 September 1848) describes the death of “Dr Couchman,” known as the “Pluckley Prophet.” It ridiculed both his followers and his alleged powers, calling him an impostor. His patients, the article notes, often “believed they were cured” until experience proved otherwise. Such attacks illustrate the growing divide between folk belief and medical modernity.

Healing, however, was not the only power ascribed to seventh sons. They were also believed to possess the gift of divination. In 19th-century Cornwall, for example, miners used divining rods – tools said to locate copper ore – exclusively entrusted to seventh sons of seventh sons. The rods had to be cut from hazel or hawthorn and used only under specific mystical conditions. These practices reveal a ceremonial and symbolic system deeply embedded in local culture, according to the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, also in 1848.

Folklore further extended the powers of seventh sons to include controlling supernatural beings. Irish legend held that only a seventh son of a seventh son could subdue a leprechaun, whose obedience could be commanded simply through eye contact. An 1849 report in the Manchester Times described how such a gaze held irresistible fascination for the elusive Loughreyman (leprechaun).

Some tales stretched into humour and satire. An 1838 article suggests that a seventh son could cure a quarrelsome spouse – either by magic or, jokingly, by always agreeing with his wife. Meanwhile, commercial products like Page’s Cod Liver Oil Pills used this tradition in marketing. A fictional testimonial featured a young man whose healing knowledge – attributed to being a seventh son of a seventh son – convinces his father to try the product. After the father’s miraculous recovery, the son becomes a business partner in the company (Nottingham Review, 19 September 1851). This illustrates how folklore was commodified in popular advertising.

While many supernatural powers were attributed to individuals of unusual birth, the seventh son figure remained perhaps the most enduring. Children born with a caul, those born feet-first, or surviving twins (the “left-twin”) were also believed to have special powers. Left-twins, for instance, were thought to cure thrush by blowing three times into the mouth of someone of the opposite sex, symbolizing a transfer of the deceased twin’s life force.

Nonetheless, the legend of the seventh son outlasted most others. In the 19th and 20th centuries, belief in their gifts sometimes motivated families to encourage their seventh sons to study medicine formally – blending folk tradition with professional practice. In doing so, the healer transitioned from outsider to insider, from folklore to medical orthodoxy.

The seventh son of a seventh son has stood as a powerful cultural symbol for centuries – one rooted in numerological mysticism, familial tradition, and communal belief. Though the age of kings and strokers has passed, the symbolic power of this figure endures in literature, music, and alternative healing today. Whether as healer, seer, or mythic archetype, the seventh son invites ongoing exploration of how we understand health, power, and identity – both in the past and the present.

Further reading:

- Davies, O. ‘Cunning-Folk in England and Wales during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’. Rural History 8 (1997): 91–107

- Davies, O. ‘Charmers and Charming in England and Wales from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century’. Folklore 109 (1998): 41–52.

- Davies, O. ‘Cunning Folk in the Medical Market-Place during the Nineteenth Century’. Medical History 43 (1999): 55–73.

- Davies, O. Popular Magic. Cunning-Folk in English History, 2007

- Huston, Arthur E. ‘The Seventh Son as a Healer’. Western Folklore 16 (1957): 56–58.

- Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Dictionary. 6 vols., 1898–1905

Leave a Reply