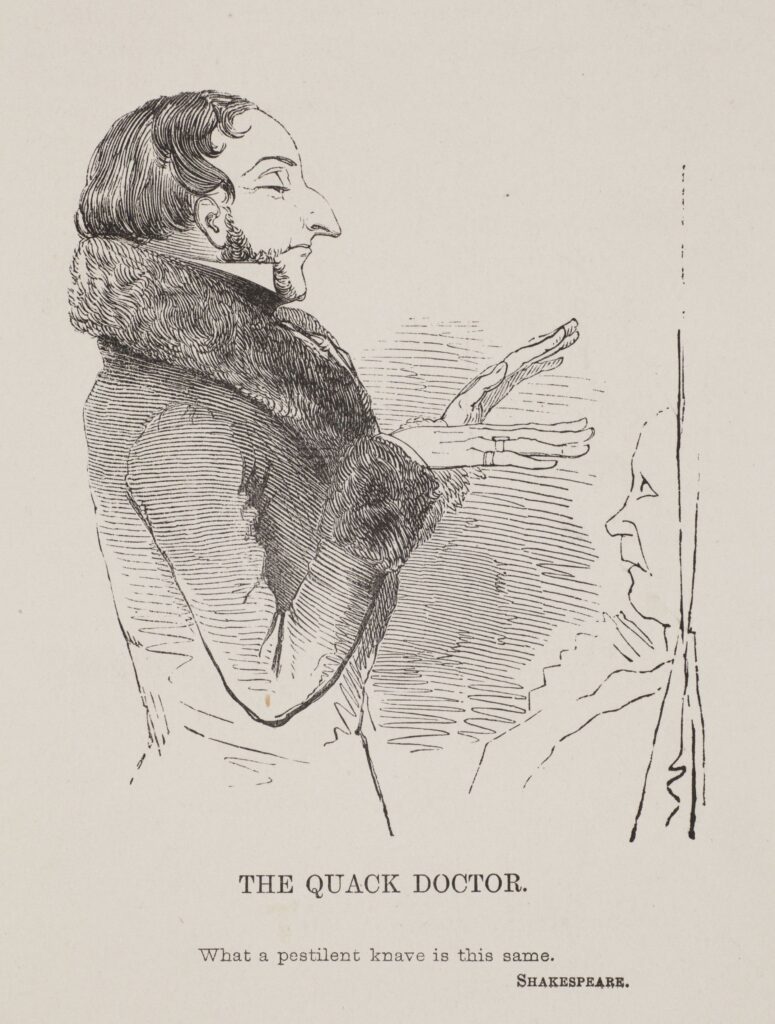

Undated illustration from the Yale University Library Collection

This is the second part of our guest blog from Julie Moore on the life and career of Isaac Chamberlain, a notorious herbalist and ‘quack doctor’ from Hertfordshire, England…

Chamberlain does not seem to have been deterred by his experience before the court, which was probably fortunate as he would be called to appear at a further five inquests to defend his conduct. He was frequently chastised, as for example in 1857 following a verdict of ‘Death from Natural Causes – Inflammation of the Bowels’ on the death of 15-year-old James Hart, the ‘boy of all work’ for a Hertford chemist. The Coroner called Chamberlain back after the verdict had been delivered and told him that his situation would have been much worse if it had been possible to prove that the various medicines that he had prescribed, including purges, had caused the boy’s death. He had been requested by the jury to call on Chamberlain ‘to abstain from practising a profession for which you are not qualified by education, and certainly not by law’. Unbowed, Chamberlain responded:

You know very well I’ve been visited by the first gentlemen in the land, and I’ve cured cases after they’ve been given up by eminent medical men – that can be well proved. (Herts Mercury 18th April 1857)

Such admonitions by the Coroner and Jury do not seem to have adversely affected Chamberlain’s career. In July 1867 he was again before the courts on a charge of the manslaughter of 32-year-old Mary Ann Parish. She had been suffering from a tumour on her shoulder and Chamberlain had prescribed an ointment containing arsenic. The prosecution claimed that such ointments were no longer deemed safe by English doctors and so he was guilty of culpable negligence. The defence argued that such treatments were still standard practice in France and America, and that Mary Ann had not followed the instructions given to her and had used too much of the ointment. Chamberlain himself did not testify. The jury found him ‘Not Guilty’. Reporting the case, the Herts Guardian commented:

The acquittal of Mr. Isaac Chamberlain has given great and general satisfaction to the public. A crowd of persons gathered round him as he left the Court and followed him to his house. The poor especially are highly pleased. A great many were in and around his door on Saturday night up to 11 o’clock, and later, obtaining medicine and advice in advance, lest they should not have a chance for some time after the Assizes. We are glad their fears proved groundless. (20th July 1867)

The nervousness around the possibility of a guilty verdict was shared by Chamberlain himself. Under the misapprehension that his goods would be forfeit should he be sentenced to prison, he signed over the considerable sum of £2,194 4s 6d in Consols to Mary Ann Chandler, his common law wife of 22 years. The relationship with Mary Ann would seem to have broken down not long after as, following the verdict, Chamberlain went to his broker and tried to get the money returned to him.

At this stage he seems to have been guilty more of naivety than fraud, as he freely admitted that the woman accompanying him was his sister, Caroline Judd, and that he had not spoken to Mary Ann. He was indignant that he could not simply reclaim his own money. He was told to go away and get Mary Ann’s agreement to the transfer but instead a few months later he presented himself at the Bank of England, together with Caroline, and this time the role of Mary Ann Chandler was played by Chamberlain’s pill box maker, Ann Hutchinson of Bethnal Green. The preliminary forms were signed but at the last minute doubts about the signature halted the final transfer. Chamberlain, Judd and Hutchinson were indicted for forgery and in May 1869, all three were in the dock in the Old Bailey. In a last-ditch attempt to forestall his arrest, Chamberlain had proposed marriage to Mary Ann, but to no avail. (Hertford Mercury 24th April 1869)

Chamberlain’s argument was that the money involved was his own, and that it had always been understood by Chandler that it was to be returned if he were acquitted or after he had served his sentence. The argument that this was only an attempt to retrieve his own property convinced the jury and all three defendants were found Not Guilty. The defence brought forward a number of Hertford residents as character witnesses, including William Pollard, the sympathetic editor of the Herts Guardian.

By now in his late sixties, Chamberlain seems to have begun to tire of the limelight. His last entry as ‘Herbalist’ appeared in the 1874 Kelly’s Trade Directory, and he died five years later, in 1879, aged 78. The generous obituary given to him by the Herts Guardian listed many of the people who, it was claimed, were healed by him after more illustrious medical men had failed. He died leaving a personal estate of under £3,000. However, the name of Chamberlain did not disappear from the list of traders following his death. His nephew, David, formerly a gunsmith, took on the business and was still listed as a herbalist in the 1911 census, aged 70.

After half a century of controversy, notoriety and fame, the career of Isaac Chamberlain shows just how much faith the English public placed in ‘irregular’ healers throughout the 19th century, despite the considerable efforts of the medical establishment (ably assisted by elements of the press) to ridicule, condemn and, ultimately, to eradicate them.