On November the 1st, 1888, an intriguing headline on page 11 of The Shrewsbury Chronicle read:

LIKE THE VISIT OF A SECOND CHRIST

It was followed by a testimonial from the Reverend F. Childerhouse for a company called Sequah Ltd.:

Gentlemen,

I am happy to inform you that I have seen some of the recipients, and they have testified to me of the great benefit they have received from your medicine. I cannot express to you the gratitude of their hearts, either by tongue or pen. Your visit to Middlesbrough is something like that of a second Christ. The lame have been made to walk, the crooked have been made straight, sad hearts cheered, and the hungry fed, and the naked clothed. I presume your name will never be forgotten by the inhabitants of Middlesbrough and North Ormesby, and especially the poor and suffering.

Yours truly,

Rev. F. Childerhouse.

This testimonial, prominently displayed on a full-page spread titled “Sequah Speaks!”, was accompanied by many others from members of the public and clergy in Middlesbrough, all praising Sequah’s alleged miracle cures and his charitable work among the poor.

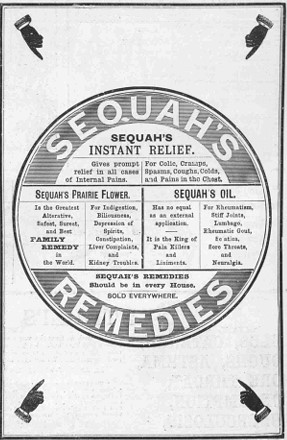

In 1889, the Bradford Observer reported on Sequah’s public demonstrations at Bradford, which were characterised by elaborate daily parades featuring a gilded chariot, assistants dressed in “prairie attire”, and musical performances. These events drew substantial crowds, reportedly reaching up to 30,000 people, regardless of adverse weather. Sequah captivated audiences by performing free, fast and apparently painless tooth extractions with his patented forceps, followed by promoting his medicinal products: “Sequah’s Indian Oil” and “Sequah’s Prairie Flower”. Marketed as natural treatments inspired by Native American practices, they were claimed to alleviate rheumatism and digestive disorders. Dramatic accounts of individuals with severe rheumatism walking unaided after treatment further bolstered Sequah’s reputation as a healer and community benefactor.

Sequah’s origins and life story were shrouded in mystery and self-proclaimed myths. At a dinner in London in June 1890 he was introduced as Canadian, though he had offered varying narratives about his past. He once claimed to have been born in Rochester, New York, in 1862, and later to have moved to Chicago. To a Brighton journalist, he said his grandfather was an English stagecoach driver (records show his grandfather was in fact a coachman) and maintained that he was born in New York. In 1908 he told a Dundee journalist he was from Bankfoot, Perthshire, and had adopted the name ‘Sequah’ professionally.

Sequah also gave inconsistent accounts of his career. He claimed in Oldham to have been apprenticed to a chemist, travelled westwards, and lived with Native Americans, learning their healing techniques. He promoted remedies inspired by their methods, such as oils made from ingredients like silver seal blubber and river fish. Alternatively, in Dundee in 1888, he omitted these stories, claiming instead to have worked across North America, farmed in Ontario, speculated in oil, and practiced medicine. He also claimed to have learned to blend botanical and mineral ingredients from “North American Indians”, creating remedies which he promoted worldwide.

Sequah, who probably took his name from ‘Sequoyah’, the polymath (1821–1843) who developed the Cherokee syllabary, was in fact born William Hartley in Liverpool in 1857. He was the son of Yorkshire-born Richard Steel Hartley (1827–1864) and Northamptonshire-born Sarah Ann White, later Lambert (1832–1910). William was raised on a 20-acre farm at Brunthwaite, Silsden (Yorkshire), managed by his mother and paternal grandfather, which, by 1930, had been in the Hartley family for 300 years.

The 1871 census shows William, aged 13, living at Keighley, at a house in Brunswick Street. He was apprenticed to nail and clog maker George Barron. Evidence suggests that, as a teenager, he travelled to America seeking adventure. Whilst there, he was likely influenced by the many ‘American-Indian’ medicine companies, and these seem to have inspired his entrepreneurial ambitions.

The exact date of his return to England is unclear, but newspapers and articles in the Chemist and Druggist confirm that his first successful public performance as “Sequah” took place in September 1887 at Landport, Portsmouth. By June 1888, he had firmly established his reputation in Dublin, where his trade flourished. Reports from the time, albeit potentially exaggerated, claimed daily earnings of £150, monthly revenues of £5,000, and profits of £8,000 over three weeks. Between 1887 and 1890, his business expanded rapidly, requiring the recruitment of associates, including 23 ‘Sequahs’ operating simultaneously across the country. In 1889, ‘Sequah Ltd.’ was incorporated, with a head office in London and Hartley as its managing director.

Promotional materials for the company stated a capital of £300,000 and reported sales of 1,458,702 bottles of Sequah’s products between June 1889 and May 1890. The net profit for the year ending 31 May 1890 was reportedly £44,585—equivalent to £4.8 million in today’s terms, reflecting the immense success of Hartley’s enterprise.

The success of Sequah Ltd. can be attributed to many factors, a key element being Hartley’s entrepreneurial vision, complemented by the expertise of James Norman, the company’s general manager. Norman, a former fairground professional and proprietor of a travelling freak show, significantly enhanced Hartley’s original roadshow by developing marketing strategies that attracted diverse audiences. Their approach combined miraculous cures, affordable medicines, and Wild West-style entertainment, creating a near-cult following.

The company’s success was further bolstered by extensive advertising through newspapers and innovative handbills, which generated widespread interest and large gatherings occasionally leading to public unrest and police intervention. Hartley’s aggressive pursuit of legal action against imitators also ensured the brand’s prominence and longevity in the 19th-century proprietary medicine market.

Additionally, Hartley engaged in strategic charitable initiatives across the country, which helped mitigate criticism of his less ethical practices. Notable examples included raising significant funds for various institutions, such as the Yorkshire Fine Art and Industrial Institution and the Industrial Institute for the Blind, and supporting hospitals like the Beckett Hospital in Barnsley. Furthermore, he provided remedies to impoverished individuals for free, further enhancing his reputation for philanthropy.

Despite his popularity, Hartley and Sequah Ltd. faced significant opposition from rivals and the authorities, including the police, magistrates, and pharmacists. A major adversary, the Commissioners of the Inland Revenue, alongside potential market saturation, played a decisive role in the company’s demise. The introduction of Section 9 of the Customs and Inland Revenue Act of 1890 was particularly damaging. This legislation restricted trade licenses to fixed premises, effectively prohibiting itinerant operations such as Sequah’s innovative and successful roadshows which were conducted from carts and mobile stands. The new law dealt a severe financial blow to Sequah Ltd., and while Hartley and his associates attempted to sustain the business by operating outside England and Europe, these efforts proved financially unsustainable. By 1895, the company had been wound up, and even its largest shareholders, including Hartley and his mother, suffered significant financial losses.

Following the collapse of Sequah Ltd., Hartley pursued a modest career as a medical botanist from 1905 to 1911 in Southampton. By 1916, he was at Foster’s Dental Surgery in Selby, Yorkshire, before moving to Sherwood Street, London, where he lived until his death on 16 January 1924. Once a larger-than-life figure who amassed considerable wealth, Hartley died quietly, leaving an estate valued at only £734. The cremated remains of the Great Sequah rest to this day in St. James’ Churchyard, Silsden, Yorkshire.

For more on the life of Sequah, see:

- W. Schupbach, ‘Illustrations from the Wellcome Institute Library. Sequah: An English “American Medicine”-man in 1890’, Medical History, 29 (1985), 272-317.

- C. Alvin, ‘Sequah: An American-Indian Medicine Man in Bradford’, The Bradford Antiquity, 16 (2012), 29-48