On 15 June 1887, James G. Hutchinson, the Coroner for Bradford in West Yorkshire, recorded a verdict in the case of the death of Alfred Priestly. The 36-year-old had fallen ill at work. Coming home he “he shivered and took some Composition when he went to Bed”. In this case the word composition refers to self-dosing, almost certainly with a laudanum-based medicine. It did him little good: “On Saturday morning he was sweating very much and said he could not get up”. Priestly “had some nitre and Hysop Tea” but (and after seeing a poor law doctor) was soon dead. Rapid deaths like this were a commonplace for the poor, though it is rather rarer to see the self-dosing that is revealed in this case.

The issue for the Coroner was why Priestly died and whether the New Poor Law could and should have done more to prevent that death, which is why correspondence about him has ended up in one of our core collections, MH12 at the National Archives. This series, with some 16,000 volumes each up to a foot thick, collects together all correspondence between officials, paupers and advocates and the central welfare authorities between 1834 and the early 1900s. The records afford a remarkable insight into the health, medical treatments and deaths of the dependent poor. In this context there has been much work on the formally qualified men – Medical Officers – who dealt with the day-to-day needs of the sick poor.

But these records also tell us much about informal medical practitioners, self-dosing (as we have seen) and the nature of the medical world in which the poor were enmeshed. The case of Priestly is in this sense important because it locates a narrative that has deep roots going back into the earliest stages of the New Poor Law, the concept of the poor (in health and medicine terms) as animals.

Thus, the Coroner in this case objected to the neglect and bad advice given by the poor law doctor. Attached to his letter was an annotated article “from the current number of the British Medical Journal”, which the Coroner felt had “bearing upon the subject” and was dated “July Aug 2nd /87″. The article was on the “toxic properties of the urine of different animals, and the influence of fasting and of a milk-diet thereon.” We learn about the urine of rabbits, guinea-pigs, dogs compared to that of humans, and that”the utility of a milk-diet in affections accompanied by intoxication is universally recognised.” In short, the Medical Officer had failed in knowing the most modern science in reference to the animal kingdom and Priestly paid the price (TNA MH12/14754,67711/1887, Letter and minutes of evidence, 15 June 1887).

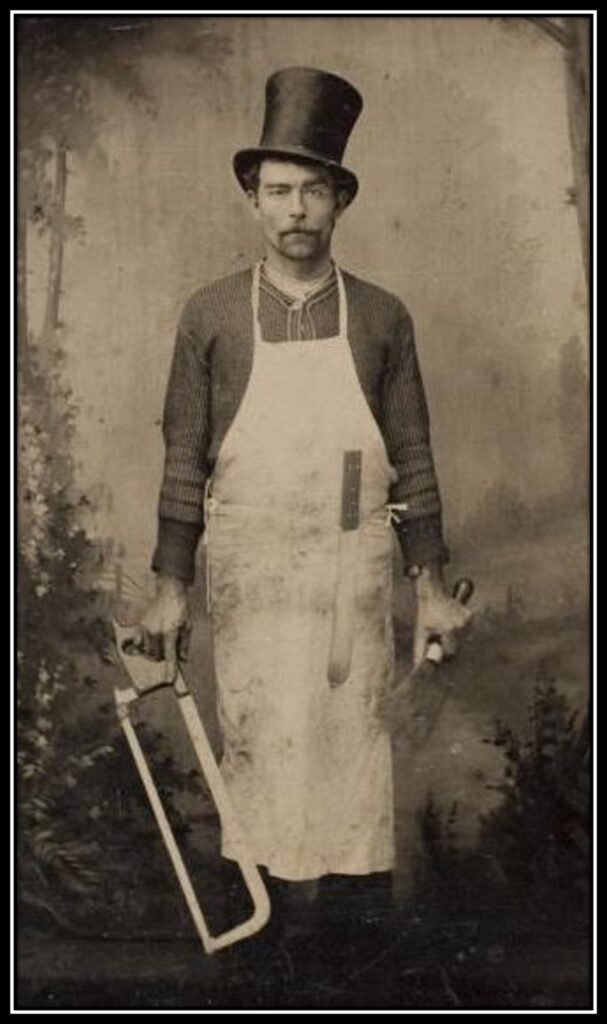

True or not, the rhetorical and practical elision of paupers and animals is a consistent them in the nineteenth century poor law. It is thus unsurprising to see butchers, farriers and others who dealt with animals seeking to intervene in the medical care of paupers. Moving to the opposite chronological end of the New poor Law, we can dwell upon the remarkable case of Henry Eliazer Robinson.

We first encounter him writing to the central welfare authorities from Altrincham (Cheshire) on 3 June 1843, less than a decade into the New Poor Law. He was then serving the role of workhouse master, having previously been a butcher and slaughterman. Responding to pauper complaints that he had deliberately kept them on short rations, left them in verminous clothing and denied food and medicines ordered by the Medical Officers, he justified himself thus:

Gentlemen, As it is more than probable that my vacation of office will be final it is my desire to place on record my opinion of the Pauper treatment in the Workhouse formed by 16 years official experiences in different parishes in various Counties South and North. To me it seems that all that is to be complained of is the idleness and extravagance of the Paupers. Few women can consume the quantities of provisions furnished to them. If those who raised the clamour had witnessed such scenes as constantly are before me, they would see that the Pauper Women are rather crammed than clammed. Never were such daintiness and extravagant waste witnessed in any private family as they exhibit daily.

The central staff were singularly unimpressed, writing on the letter: “This [Mr.] Robinson is a self sufficiently talking, scribbling Fool – and I hope he will not get another place as a Wk.Ho [master], for I am sure he is not a good one.” (TNA MH12/771,7842/B/1843, Letter, 3 June 1843)

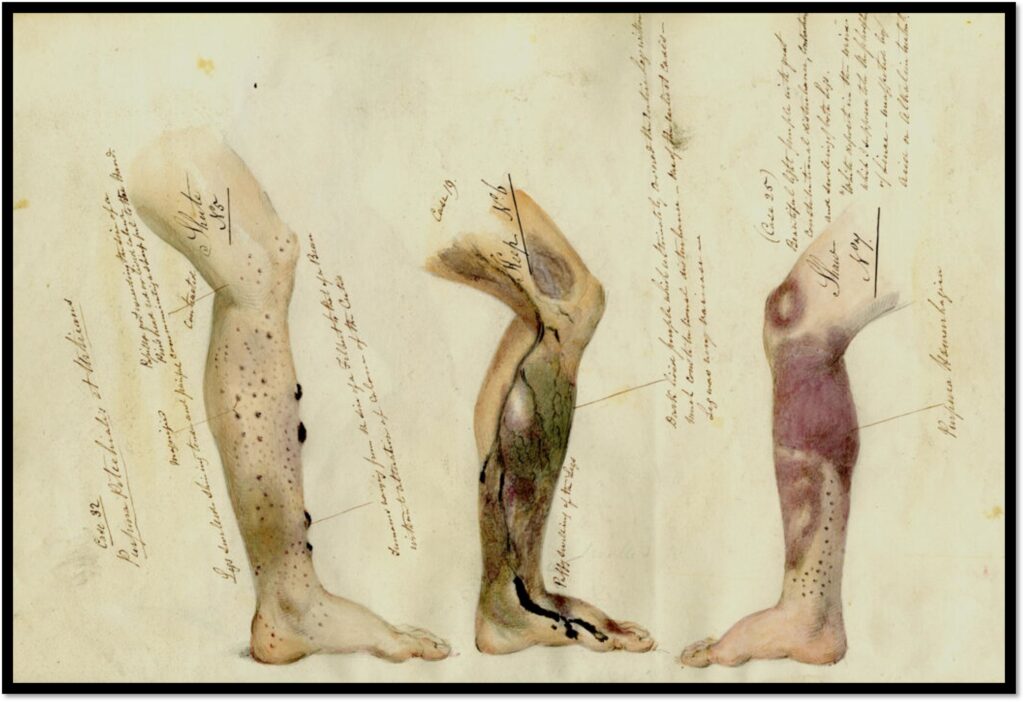

They were not to get their wish. In July 1843, Robinson sought both the further defend his record and to stay in post. Noting a report of 4 December 1840 “to which access has been obtained by me” he told the story of a “cutaneous disease [that] existed more or less in this Establishment to the time of my entering on office. It then prevailed to so great an extent as to have infected the greater part of the children.” Casting himself in an heroic mould (and ignoring the fact that dealing with such disease in the workhouse was actually the province of the trained Medical Officer) he set about effecting a cure.

Robinson felt able to do so because:

Being by trade a Butcher consequently having some acquaintance with the anatomy and physiology of the animal system, as well as much experience in a Workhouse of cutaneous diseases, and arguing analogically a conviction was carried to my mind that it was not the itch; was not induced as the itch; nor would yield to the usual remedies for the itch. To me it rather seemed to proceed from similar causes and to partake of the character of the scurvy, or in the mere animal system, the mange.

Secure in his background as a butcher he felt that the cause of the skin problems was that the workhouse inmates had been overfed compared to what they were used to having outside, such that “improper articles were introduced into the blood; the want of exercise not causing sufficient perspiration to carry off the crudities, and the cold dampness of the atmospheric air from the quantity of humidity with which we are surrounded.” He had thus placed the children on a programme of exercise, “warm baths every saturday for boys & girls”, and an “internal medicine” of his own devising, a regime which proved very successful such that “so far as I can learn there is not this day any eruptive case in the Establishment.”

Against the background of such success this irregular healer now sought the approbation of the central authorities to override the Medical Officer and other staff an impose a new medical regime:

Knowing that when animals are taken from poor keep to good it is usual to administer medicine, I would most respectfully submit, by the Sanction and Authority of the Commissioners, to the Gentlemen of the Medical Profession whether it be not expedient to administer a little cleansing medicine to the Paupers, especially the children on their admission to the Workhouse.

Lest anyone think of him as an offensive quack, Robinson added a postscript, arguing that:

I trust no fastidious person will be offended because Paupers and mere animals are named. It should be borne in mind that it is only of mere animal system that any acquaintance is testified by me, and that the suggestions cause me to speak analogically of the farmer, leaving out the superior faculties & power of mankind (TNA MH12/771,10149/B/1843, Letter 17 July 1843).

There is no evidence that the central authorities objected either to the elision or the deployment of Robinson’s cleansing medicine. Evidently the local authorities felt the same for he continued in post at Altrincham for a further five years. Fanning out from this case, we can see that the rhetorical and practical shading of the boundary between ‘animal’ and ‘pauper’ afforded some of the spaces within which irregular medicine might be practiced at the very heart of one of the core functions of the nineteenth-century British state.